The Impact of Automation on Sewing Machine Design

There's a quiet romance to antique sewing machines. It’s not just about the beauty of their cast-iron frames or the intricate details of their decorative elements. It’s about the *feeling* they evoke – a sense of connection to a time when objects were crafted with painstaking care, a time when ingenuity and practicality intertwined to create tools that empowered generations. My grandmother, Elsie, had a Singer 66, a black beauty that hummed with the promise of creation. I remember sitting at her feet as she mended clothes and fashioned quilts, the rhythmic click and whir a comforting lullaby. That machine wasn't just a tool; it was a portal to her stories, her resilience, and a tangible link to my family's history. Thinking about that machine, and countless others like it, makes you wonder about the forces that shaped them – and the dramatic shift that automation brought to their design.

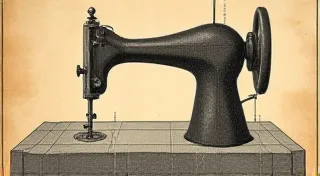

For much of the 19th century, sewing was a laborious, time-consuming task done entirely by hand. The invention of the sewing machine in the mid-1800s, primarily through the efforts of Elias Howe and Isaac Singer, was revolutionary. The earliest machines, while vastly superior to hand sewing, were still quite basic. They were marvels of mechanical engineering, yes, but also quite temperamental. Imagine the ingenuity required to design a machine that could consistently pierce fabric and interlock thread, all using complex levers, cams, and gears! These initial machines were often large, heavy, and required a fair bit of skill to operate. The design prioritized function; aesthetics were secondary, though the makers still incorporated decorative elements – ornate decals, detailed knobs, and elegantly curved bases – as a mark of quality and a touch of Victorian refinement.

The Rise of Mass Production & Standardization

The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the beginning of truly mass production. The need to manufacture sewing machines faster and more efficiently led to a significant change in their design philosophy. While early machines were often hand-fitted and customized, the burgeoning factory system demanded standardization. Interchangeable parts became the norm, simplifying assembly and repair. This also meant a shift away from the heavily ornamented, almost handcrafted aesthetic of the earlier machines. The emphasis moved to robustness, reliability, and ease of manufacture.

Manufacturers began using stronger, simpler materials. Cast iron remained popular for its strength, but the elaborate, swirling bases and decorative flourishes started to disappear. The focus shifted to functionality and reducing production costs. The aesthetic became more utilitarian, though manufacturers still attempted to maintain a semblance of visual appeal. These "transitional" machines – those produced roughly between 1890 and 1920 – represent a fascinating bridge between the handcrafted elegance of the past and the streamlined efficiency of the future.

The Electric Revolution and its Design Consequences

The introduction of electric motors in the 1920s and 1930s marked another pivotal moment. Suddenly, the need for treadles and hand cranks vanished. This immediately impacted the machines' silhouettes. The large, robust treadle base, once a defining characteristic, was no longer necessary. The machines became lighter, smaller, and, arguably, less imposing. This also allowed for experimentation with new materials and designs.

Enamel became a popular finish, replacing the black paint and often accompanied by brighter, more fashionable colors. Streamlined Art Deco designs – inspired by automobiles and trains – began to influence the machines' appearance. Manufacturers like Singer and Brother embraced these trends, producing machines with sleek, modern lines. While some lamented the loss of the "old-world charm," the new designs reflected the optimism and modernity of the era. The electric motor wasn’t just about convenience; it was a symbol of progress.

The Post-War Era: Plastics and Simplicity

The post-World War II era brought about even more radical changes. The advent of plastics and advanced manufacturing techniques led to a further simplification of design. More parts were molded from plastic, reducing weight and cost. The complex internal mechanisms became more enclosed, and the decorative elements disappeared almost entirely. The focus was now solely on mass production and affordability. These machines, while reliable and functional, often lack the aesthetic appeal of their predecessors. They represent the culmination of the relentless march of automation.

Looking back at Elsie’s Singer 66, a machine made in the 1920s, it’s easy to appreciate the craftsmanship that went into its creation. The weight of the cast iron, the precision of the gears, the satisfying click of the needle – these are things that are largely absent from modern sewing machines. While modern machines offer features like automatic threading and stitch selection, there’s something irreplaceable about the connection one feels to a machine that represents a different era, an era when objects were made with care and a sense of pride.

Collecting and Appreciation

For collectors of antique sewing machines, understanding the impact of automation is crucial for appreciating the evolution of these fascinating objects. Each machine tells a story – a story of technological innovation, changing design aesthetics, and the enduring human desire to create. Recognizing the subtle nuances between a hand-fitted Victorian machine and a mass-produced, plastic-encased model allows us to truly value the unique characteristics of each one. It’s not just about owning a piece of history; it’s about preserving a legacy of ingenuity and craftsmanship.

My grandmother's Singer 66 isn't just a sewing machine; it's a tangible reminder of her life, her skills, and her connection to a time when things were made differently. And that, perhaps, is the greatest value of collecting vintage sewing machines – the opportunity to connect with the past and to appreciate the beauty and ingenuity of those who came before us.